mod323 · June 29th, 2022

Water Clocks and the Beanstalk Helmsman

Part 2: Peg maintenance

Check out Part 1 in this series about Beanstalk: Protocol-Native Utility

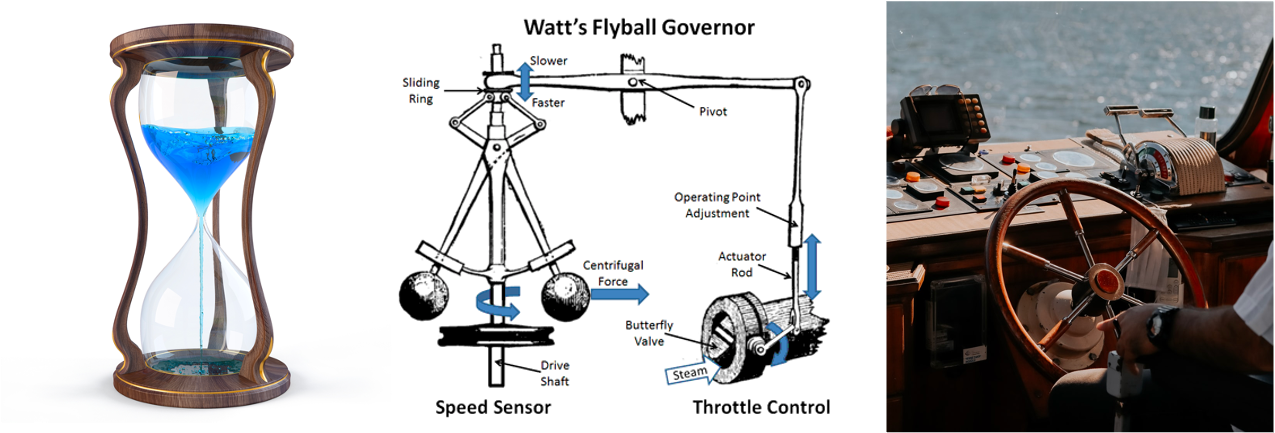

Control systems, systems that provide a desired response by controlling an output, are believed to have been in use since ancient times. The Ancient Egyptians, for example, controlled the flow of water to measure time. The concept of water clocks was simple—two clay pots, one filled with water and a hole at the bottom. The hole served as a controller, depending on its size it controlled the amount of water that passed through it.

The first automatic control system, the centrifugal governor, was invented by Christiaan Huygens in the 17th century and was used to regulate the distance and pressure between millstones in windmills. James Watt adapted a governor to control his steam engine in 1788 and they continued to be widely used during the Steam Age in the 19th century. The governor controlled the speed of an engine by regulating the flow of fuel, so as to maintain a near-constant speed.

The mathematical basis of control theory was first studied by James Clerk Maxwell in his 1868 paper On Governers, but it wasn’t until 1922 when a formal control law for what we know today as a three-term control was developed by Nicolas Minorsky, while designing automatic ship steering for the US Navy. Minorksy noted that the helmsman steered the ship based not only on the current course error but also on past error, as well as the rate of change. You might have heard of this as a PID (Proportional, Integral, Derivative) controller; it's how cruise control works in modern cars.

But what do controllers have to do with Beanstalk?

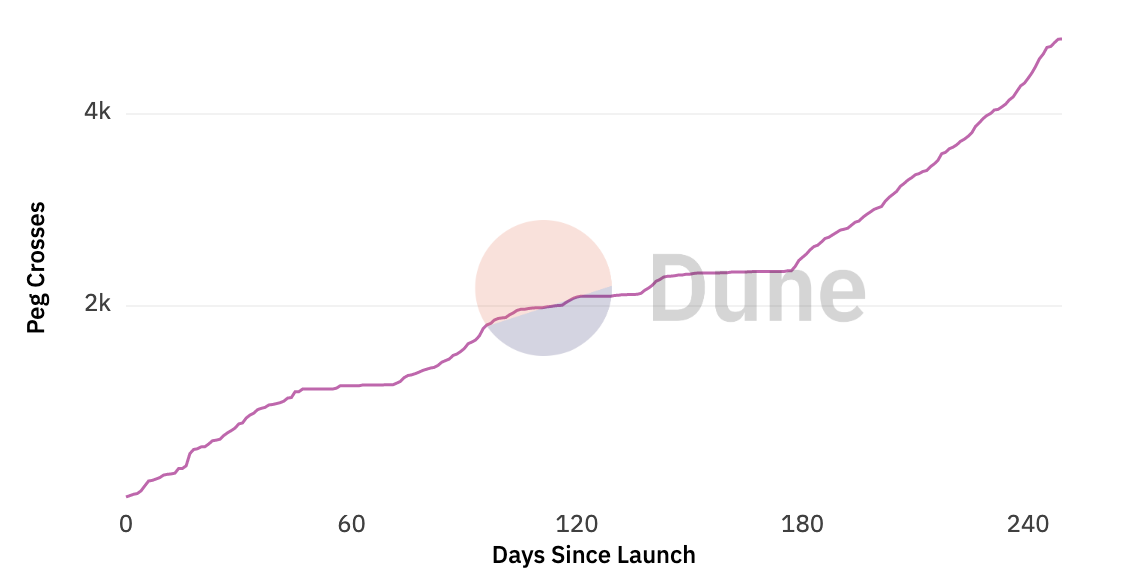

Beanstalk uses two controllers to regularly cross the price of Bean over peg:

- Mint the shortage of Beans in the liquidity pool when P > 1; and

- Regulate the interest rate (the Temperature) for Sowing Beans in the Field (Beanstalk’s credit facility).

The minting controller is a simple proportional controller (similar to the governor used by Watt) which measures the error from peg—in this case, the shortage of Beans in the liquidity pool—and mints it. The larger the error, or shortage, the larger the number of Beans minted.

It’s at the Field however, where economics and control theory meet.

The Field

The Field’s objective is to remove excess Beans in the liquidity pool. It does this by issuing Soil. Anytime there’s Soil, Beanstalk is willing to borrow Beans in exchange for Pods (Beanstalk’s debt native asset). The question is, at what Temperature? It might feel intuitive at first to link it to the price of Bean (or the amount that needs to be removed) through a proportional controller, i.e. the larger the deviation from peg, the higher the Temperature, right?

While in theory that may work, Beanstalk separates the markets of Bean and Soil to avoid:

- Manipulation of the Temperature through manipulating the price of Bean; and

- A negative feedback loop where larger deviations from peg create larger changes in Temperature and accordingly the debt issued, increasing the odds of a death spiral.

Instead, the Field looks at three things to determine how to adjust the Temperature:

- If the price of Bean is above or below peg;

- If the debt of Beanstalk is above or below a threshold; and

- the rate of change in demand for Soil.

The last one is the derivative term in a controller. The same rate of change that the helmsman accounted for when steering the ship.

A derivative term does not consider the magnitude of the error, this means that while it can move a system towards a direction, it can’t bring the error to zero.

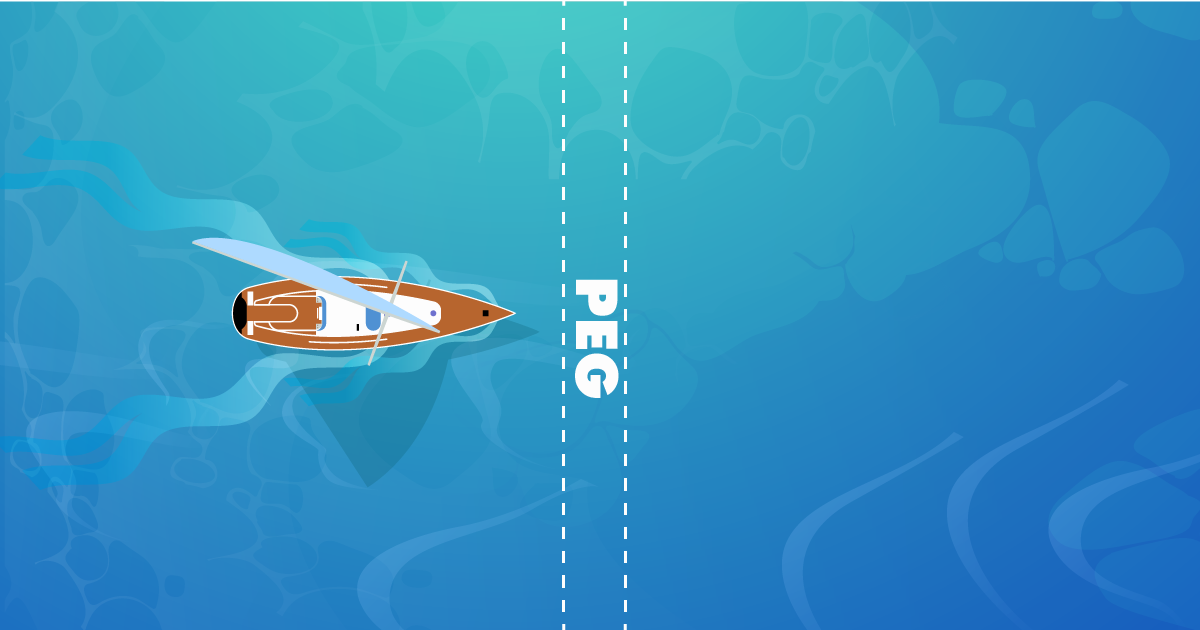

Beanstalk doesn’t try to bring Bean to peg, it tries to cross it.

If Beanstalk was a ship, it would be steered by a helmsman that only knows their relative position to destination and whether the ship is accelerating or decelerating towards or away from it. But never how fast the ship is sailing, nor how close or far they are from their destination. Back and forth, regularly crossing it.

Soil

Demand for Soil, or the rate of change of it, is an elegant way to control the Temperature, but doesn’t come without limitations.

Demand for Soil can only be measured by selling Soil, which comes at the expense of debt issuance. This means that, in theory, for the Field to always perfectly measure changes in demand, then there needs to be infinite Soil available.

Beanstalk initially sought to solve this problem by having the Soil available be the cumulative of the excess of Beans in the liquidity pool over multiple seasons bounded by a minimum and a maximum Soil that was a percent of the total Bean supply. This soon proved problematic as it led the protocol to take on large amounts of debt when P > 1 (i.e., the very time where no Beans need to be removed from the supply).

Soil issuance has been optimized through a series of BIPs (here and here) that have dramatically improved the efficiency of the Soil market. The maximum available Soil at any season now is equal to the excess of Beans in the liquidity pool and the minimum is a function of the Temperature and debt paid back. However, limiting the amount of Soil minted each Season limits the protocol’s ability to measure demand for Soil, especially at times when it sells out Season over Season. When that happens, the protocol switches to a time-based formula that compares how long it took for Soil to sell out within a given Season.

* * *

Beanstalk’s credit facility and its ability to properly price the Temperature is foundational not only to peg maintenance but also a healthy debt level. A delicate balance between issuing the right amount of Soil at the right Temperature. So how has it performed? The proof is in the pudding.